This is an old revision of the document!

Real Analog: Chapter 12

12. Introduction and Chapter Objectives

In this chapter we will address the issue of power transmission via sinusoidal (or AC) signals. This topic is extremely important, since the vast majority of power transmission in the world is performed using AC voltages and currents.

For the most part, the topic of AC power transmission focuses on the average power delivered to a load over time. In general, it is not productive to focus on the power transmission at a particular time since, if the load contains energy storage elements (such as capacitors and inductors), it is possible that at times the load will absorb power and at other times the load will release power. This characteristic leads to the concepts of average power and reactive power – average power is typically the power that is converted by the load to useful work, while reactive power is the power that is simply exchanged by energy storage elements. Power companies cannot really charge customers for power which is not absorbed by the load, so one primary goal in AC power transmission is to reduce the reactive power that is sent to the load.

In this chapter we introduce the basic topics relative to calculation of AC power. In section 12.1, we introduce the basic concepts associated with AC power, including the notion that a load containing energy storage elements may alternately absorb and release power. This discussion will lead to the concepts of average power and reactive power, which are discussed in section 12.2. Power calculations are often presented in terms of RMS values; these are introduced in section12.3. The relative roles of average and reactive power are often characterized by the apparent power and the power factor, which are presented in section 12.4. In section 12.5, we will use complex numbers to simultaneously quantify the average power, the reactive power, the apparent power, and the power factor. Finally, in section 12.6, we examine approaches to reduce the reactive power which is exchanged between the power company and the user. This technique is called power factor correction.

After Completing this Chapter, You Should be Able to:

- Define instantaneous power, average power, and reactive power

- Define real power, reactive power, and complex power

- Define RMS signal values and calculate the RMS value of a given sinusoidal signal

- State, from memory, the definition of power factor and calculate the power factor from a given combination of voltage and current sinusoids

- Draw a power triangle

- Correct the power factor of an inductive load to a desired value

12.1: Instantaneous Power

We will begin our study of steady-state sinusoidal power by examining the power delivered by a sinusoidal signal as a function of time. We will see that, since all the signals involved are sinusoidal, the delivered power varies sinusoidally with time. This time-varying power is called instantaneous power, since it describes the power delivered to the load at every instant in time. The instantaneous power will not, in general, be directly useful to us in later sections but it does provide the basis for understanding the concepts presented throughout this chapter.

In chapter 1, we saw that power is the product of voltage and current, so that power as a function of time is:

$$p(t)=v(t) \cdot i(t) (Eq. 12.1)$$

Power as a function of time is often called instantaneous power, since it provides the power at any instant in time. So far, this is the only type of power with which we have been concerned. If our voltages and currents are sinusoidal, as is the case for AC power, we can write $v(t)$ and $i(t)$ as:

$$v(t) = v_m \cos(\omega t + \theta_v) (Eq. 12.2)$$

And:

$$i(t) = I_m \cos(\omega t+ \theta_i) (Eq. 12.3)$$

Where, of course, $V_m$ and $\theta_v$ are the amplitude and phase angle of the voltage signal while $I_m$ and $\theta_i$ are the amplitude and phase angle of the current signal. It should be noted at this point that the voltage and current signals of equations (12.2) and (12.3) are not independent of one another. Figure 12.1 shows the overall system being analyzed – the voltage $v(t)$ and the current $i(t)$ are the voltage and current applied to some load. If the load has some impedance, $Z_L$, the voltage and current are related through this impedance. Thus, if we represent $v(t)$ and $i(t)$ in phasor form as $p(t) = v(t)$ and $i(t)=\underline{I}e^{j \omega t}$, then $\underline{V}=Z_L \cdot \underline{I}$.

Substituting equations (12.2) and (12.3) into equation (12.1) results in:

$$p(t)=V_mI_m \cos(\omega t + \theta_v) \cos(\omega t + \theta_i) (Eq. 12.4)$$

Equation (12.4) can be re-written, using some algebra and trigonometric identities, as:

$$p(t) = \frac{V_m I_m}{2} \left\{ \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i) + \cos(2 \omega t + \theta_v + \theta_i) \right\} (Eq. 12.5)$$

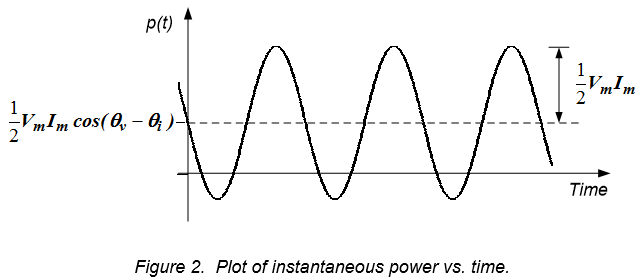

Since $V_m$, $\theta_v$, $I_m$, and $\theta_I$ are all constants, we can see that equation (12.5) is the sum of two terms: a constant value, $\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i)$, and a sinusoidal component, $\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(2 \omega t + \theta_v + \theta_i)$. The time-domain relationship of equation (12.5) is plotted in Figure 12.2. The signal's average value is $\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i)$ and has a sinusoidal component with an amplitude of $\frac{V_m I_m}{2}$.

Section Summary

- The power delivered to a load by a sinusoidal (or AC) signal has two components: an average value and a sinusoidal component.

- Both the average value and the sinusoidal component are dependent upon the amplitude and phase angles of the voltage and current delivered to the load. These values are, in turn, set by the impedance of the load.

- The average power is dissipated or absorbed by the load. This power is electrical power which is converted to heat or useful work.

- The sinusoidal component of the power is due to energy storage elements in in the load; this power is exchanged (in some sense) between the load and the system supplying power. It is purely electrical energy which the load is not using to perform useful work.

Exercises

- The current and voltage delivered to a load are $i(t) = 2 \cos(100t)$ and $v(t) = 120 \cos(100t+65^{\circ})$, respectively. Calculate the average power delivered to the load and the amplitude of the sinusoidal component of the power.

12.2: Average and Reactive Power

Examination of equation (12.5) and Figure (12.2) indicates that the instantaneous power can be either positive ornegative, so the load is alternately absorbing or releasing power. The overall amount of power absorbed vs. power released is dependent primarily upon the $\cos(\theta_v - \theta_i)$ term. If the voltage and current are in phase, $\theta_v = \theta_i$, $\cos(\theta_v - \theta_i ) = 1$ and the instantaneous power is never negative. The voltage and current have the same phase if the load is purely resistive – a resistor always absorbs power. If the voltage and current are $90^{\circ}$ out of phase, as is the case for a purely capacitive or purely inductive load, $\cos(\theta_v - \theta_i) = 0$. In this case, the instantaneous power curve is a pure sinusoid with no DC offset, so on average no power is delivered to the load. This is consistent with our models of capacitors and inductors as energy storage elements, which do not dissipate any energy.

The concepts presented in the paragraph above can be mathematically presented by rearranging equation (12.5) yet again. Application of additional trigonometric identities and performing more algebra results in:

$$p(t) = \frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i) [1+ \cos(2 \omega t)] + \frac{V_m I_m}{2} \sin(\theta_v - \theta_i) [\sin(2 \omega t)] (Eq. 12.6)$$

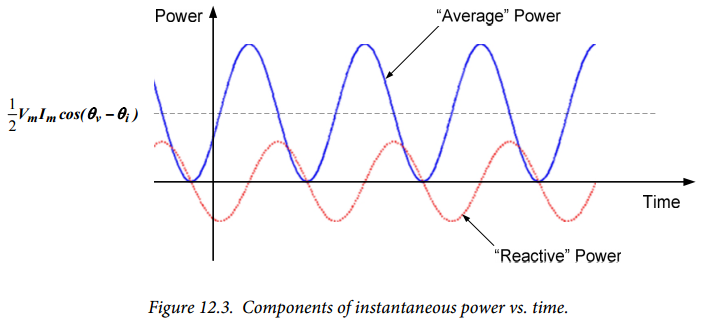

The two terms in equation (12.6) are plotted separately in Figure 12.3. The first term, $\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i) [1+ \cos(2 \omega t)]$, has an average value of $\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i)$, while the second term, $\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \sin(\theta_v - \theta_i) [ \sin(2 \omega t)]$, has an average value of zero. Thus, the average power delivered to a load is:

$$P=\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i) (Eq. 12.7)$$

The amplitude of the term $\frac{V_m I_m}{2} \sin(\theta_v - \theta_i) [ \sin(2 \omega t)]$, which provides no average power to the load, is termed the reactive power, Q:

$$Q = \frac{V_m I_m}{2} \sin(\theta_v - \theta_i) (Eq. 12.8)$$

The reactive power is a measure of the amount of power which is delivered to the load, but is not absorbed by the load – the load returns this power to the source!

Section Summary

- The average power delivered to a load is:

$$P= \frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i)$$

Where $V_m$ and $\theta_v$ are the amplitude and phase angle of the voltage while $I_m$ and $\theta_i$ are the amplitude and phase angle of the current. The average power is often also called the real power. The average power is also the power dissipated by any resistive elements in the load. Units of average power are Watts (abbreviated W).

- The reactive power dellivered to a load is:

$$Q = \frac{V_m I_m}{2} \sin(\theta_v - \theta_i)$$

The reactive power is not actually absorbed by the load; it is stored by the energy storage elements in the load and then returned to the source. The units of reactive power are taken to be Volt-Amperes Reactive (abbreviated VAR). Note that technically watts are the same as volt-amps, but we have changed terminology to avoid any confusion between real and reactive power.

Exercises

- The current and voltage delivered to a load are $i(t) = 2 \cos(100t)$ and $v(t) = 120 \cos(100t+65^{\circ})$, respectively. Calculate the average power delivered to the load and the reactive power delivered to the load.

12.3: RMS Values

In sections 12.1 and 12.2, we introduced some basic quantities relative to delivery of power using sinusoidal signals. We saw that power dissipated by a load (essentially, any energy which is converted to non-electrical energy such as heat or work) is the average power. Reactive power results from energy which is stored by capacitors and inductors in the load and is then returned to the source without dissipation.

In this chapter, we continue our study of AC power analysis. We will introduce the concept of the root-mean- square (RMS) value of a signal as a way to represent the power of a time-varying signal. We will also introduce complex power as a way to conveniently represent both average and reactive power as a single complex number. We also introduce power factor as a way to represent the efficiency of the transfer of power to a load.

It is often desirable to compare different types of time-varying signals (for example, square waves vs. triangular waves vs. sinusoidal waves) using a very simple metric. Different types of signals are often compared by their RMS (root-mean-squared) values. The general idea behind the RMS value of a time-varying signal is that we wish to determine a constant value, which delivers the same average power to a resistive load.

The average value, $P$, of an instantaneous power $p(t)$ is defined to be:

$$P = \frac{1}{T} \int^{t_0 + r}_{t_0} p(t)dt (Eq. 12.9)$$

The power delivered to a resistive load by a constant voltage or current source is, from chapter 1.1,

$$P=R \cdot I_{eff}^{2} = \frac{V^2_{eff}}{R} (Eq. 12.10)$$

$I_{eff}$ and $V_{eff}$ are the effective (or constant) current and voltage, respectively, applied to the resistive load, $R$. It is our goal to equate equations (12.9) and (12.10) to determine the effective voltage or current values, which deliver the same average power to a resistive load as some time-varying waveform.

Assuming that a current is applied to a resistive load, the instantaneous power is $p(t) = R \cdot i^2 (t)$. Substituting this into equation (12.9) and equating to equation (12.10) results in:

$$R \cdot I_{eff}^2 = \frac{1}{T} \int\limits_{t_0}^{t_0 + T} R \cdot i^2 (t)dt (Eq. 12.11)$$

Solving this for $I_{eff}$ results in:

$$I_{eff} = I_{RMS} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{T} \int\limits_{t_0}^{t_0 + T} i^2 (t)dt} (Eq. 12.12) And the effective current is the square root of the mean of the square of the time-varying current. This is also called the RMS (or root-mean-square) value, for rather obvious reasons. A similar process can be applied to the voltage across a resistive load, so that $p(t)= \frac{v^2(t)}{R}$. Equating this expression to equation (12.9) results in:

$$V_{eff} = V_{RMS} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{T} \int\limits_{t_0}^{t_0 + T} v^2 (t)dt} (Eq. 12.13)$$

So that the definition of an RMS voltage is equivalent to the definition of an RMS current.

Equations (12.12) and (12.13) are applicable to any time-varying waveform; the waveforms of interest to us are sinusoids, with zero average values (per equations (12.10) and (12.11)). In this particular case, the RMS values can be calculated to be:

$$V_{eff} = V_{RMS} = \frac{V_m}{\sqrt{2}} (Eq. 12.14)$$

And:

$$I_{eff} = I_{RMS} = \frac{I_m}{\sqrt{2}} (Eq. 12.15)$$

Where $V_m$ and $I_m$ are the peak (or maximum) values of the voltage and current waveforms, per equations (12.10) and (12.11). Please note that equations (12.14) and (12.15) are applicable only to sinusoidal signals with zero average values.

The average and reactive powers given by equations (12.16) and (12.17) can be written in terms of the RMS values of voltage and current as follows:

$$P=V_{RMS} I_{RMS} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i) (Eq. 12.16)$$

And:

$$Q = V_{RMS} I_{RMS} \sin(\theta_v - \theta_i) (Eq. 12.17)$$

Section Summary

- The RMS value of a sinusoidal signal $f(t) = F_m \cos(\omega t + \theta)$ is given by:

$$f_{RMS} = \frac{F_m}{\sqrt{2}$$

- The above formula cannot be used for any signal other than a pure sinusoid with no offset.

Exercises

- The current and voltage delivered to a load are $i(t) = 2 \cos(100t)$ and $v(t) = 120 \cos(100t+65^{\circ})$, respectively. What are the RMS values of voltage and current?

12.4: Apparent Power and Power Factor

In the previous subsections, we have seen that average power can be represented in terms of either the magnitudes of the voltage and current or the RMS values of the voltage and current and a multiplicative factor consisting of the cosine of the difference between the voltage phase and the current phase:

$$P= \frac{V_m I_m}{2} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i) = V_{RMS} I_{RMS} \cos(\theta_v - \theta_i)$$

It is sometimes convenient to think of the average power as being the product of apparent power and a power factor (abbreviated $pf$). These are defined below:

- The apparent power is defined as either $\frac{V_m I_m}{2}$ or $V_{RMS} I_{RMS}$. (The two terms are, of course, equivalent.) Units of apparent power are designated as volt-amperes (abbreviated VA) to differentiate apparent power from either average power or reactive power.

- The power factor is defined as $\cos(\theta_v - \theta_i)$. Since cosine is an even function (the sign of the function is independent of the sign of the argument), the power factor does not indicate whether the voltage is leading or lagging the current. Thus, power factor is said to be either leading (if current leads voltage) or lagging (if current lags voltage).

It should be emphasized again at this point that the voltage and current are not independent quantities; they are related by the load impedance. For the system of Figure 12.1, for example, the voltage and current phasors are:

$$\underline{V} = Z_L \cdot \underline{I} (Eq. 12.18)$$